When it comes to celebrating California art’s special relationship with progressive architecture and integrated design, Elizabeth Armstrong, the recently installed executive director of the Palm Springs Art Museum, has been walking the walk for years.

At her post since January 2015, Armstrong has done significant pioneering curatorial work in this interdisciplinary realm. Her efforts were on display in 2008, when as chief curator at the Orange County Museum of Art she produced the blockbuster exhibition Birth of the Cool: California Art, Design, and Culture at the Midcentury as well as American Moderns: Villa America, 1900–1950. The former examined art, buildings, and objects keyed to the cool jazz aesthetic, quite literally prefiguring her current role here.

“I found a copy of that catalog recently,” Armstrong says, “and the Albert Frey house famously perched above the museum campus appeared on page 4! And now Frey’s Aluminaire House from the 1930s will be installed in the new downtown park by the museum. Frey’s early sensitivity to resource scarcity and his response to social designs for living were so prescient and [are] still so relevant today.”

And just like that, her genuine enthusiasm becomes fully apparent.

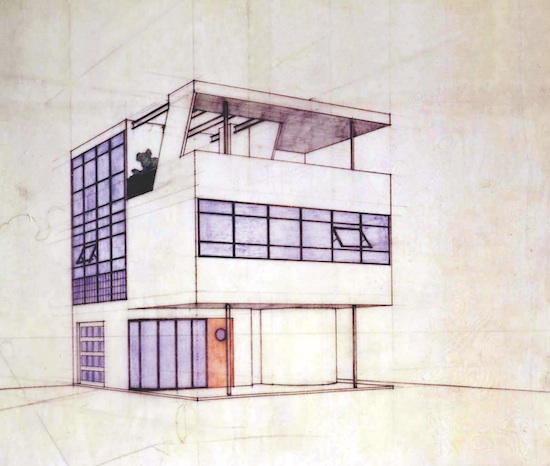

illustration courtesy of the aluminaire foundation inc.

Albert Frey's early drawing of the Aluminaire House.

“I do think I have a fairly intimate knowledge of the region’s unique architecture and design situation,” she says. “But that speaks to my appreciation for all the arts.”

Armstrong’s career trajectory includes not only salient curatorial practices, but also other aspects of public programming, audience expansion, donor engagement, historical scholarship, and strategic long-term planning. At OCMA she was acting director and initiator of the California Biennial. Her tenure as senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego saw a major emphasis on Latino culture represented in both the collection and the membership base.

Most recently, as the first curator of contemporary art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, she founded the experimental Center for Alternative Museum Practice, where contemporary artists were commissioned to create innovative and inclusive works.

While this professional history may seem to indicate a new direction in Palm Springs Art Museum’s future, two of Armstrong’s priorities have been to reinvigorate the permanent collection and the engagement of the museum with the community.

“I didn’t do any advance press,” she says. “I wanted to wait to get on the ground and gain a better sense of the museum before I started talking about my plans. But yes, I am here to shake things up, to get the Palm Springs Art Museum more actively involved in the community. My history as a curator is founded on an interest in how life and art interconnect, exploring universal themes that are accessible to real people, in real life. And that’s the kind of fresh approach I’m hoping to bring to this very special institution.”

The museum’s collection is encyclopedic, including Native American and pre-Columbian holdings, as well as modern and contemporary art and design. From early on, Armstrong has focused on rethinking how this permanent collection could function as “part of a provocative dialogue with the present, as works across time and culture speak to one another.”

To that end, she immediately convened the museum’s curators in a series of wide-ranging conversations and encouraged them to think animatedly about refreshing the permanent collection’s installation along provocative themes. Although she inherited some exhibition programming, through this discussion process she was able to insert her approach right away. Reflections on Water — ranging from 19th-century water vessels to contemporary photographs of the Salton Sea — was the first of what will be more frequent exhibitions reflecting this new urgency.

Another example of her thinking changed the scope of the upcoming show of Edward S. Curtis photographs. Her team was able to expand the show in a surprising way.

“It’s so important for the region’s connection to Curtis’ work to be documented, but also, our community is embedded in this history,” Armstrong says. “So, to augment the show, curator Daniell Cornell invited several contemporary Native American photographers — artists who have turned the camera on themselves — to respond to Curtis’ historical work. It’s powerful.”

Still Life: Capturing the Moment, at the museum’s Palm Desert location, also emerged from those staff conversations, as did Seeing the Light: Illuminating Objects at the museum’s Architecture and Design Center, which Armstrong sees as a natural venue for artists to be in dialogue with designers.

“Los Angeles has a similar history of embracing design but it’s intensified here, so we can go even deeper,” she says. “Artists all over the world are blurring art forms and disciplines with gusto, blending traditions and technologies as makers, in social practice, elevating craft, and exploring regionalism. Why shouldn’t museums do the same?”